|

Posture

The depiction of

Diplodocus posture has

changed considerably over the years. For instance, a classic 1910

reconstruction by Oliver P. Hay depicts two

Diplodocus with splayed lizard-like limbs on the

banks of a river. Hay argued that Diplodocus

had a sprawling, lizard-like gait with widely splayed legs, and was

supported by

Gustav Tornier.

However, this hypothesis was contested by W. J. Holland, who demonstrated

that a sprawling Diplodocus

would have needed a trench to pull its belly through. Finds of sauropod

footprints in the 1930s eventually put Hay's theory to rest.

Later, diplodocids were often

portrayed with their necks held high up in the air, allowing them to graze

from tall trees. Studies using computer models have shown that neutral

posture of the neck was horizontal, rather than vertical, and scientists

such as Kent Stephens have used this to argue that sauropods including

Diplodocus did not

raise their heads much above shoulder level. However, subsequent studies

demonstrated that all

tetrapods appear to

hold their necks at the maximum possible vertical extension when in a

normal, alert posture, and argued that the same would hold true for

sauropods barring any unknown, unique characteristics that set the soft

tissue anatomy of their necks apart from other animals. One of the sauropod

models in this study was Diplodocus,

which they found would have held its neck at about a 45 degree angle with

the head pointed downwards in a resting posture.

As with the related genus

Barosaurus, the very long

neck of Diplodocus

is the source of much controversy among scientists. A 1992 Columbia

University study of Diplodocid neck structure indicated that the longest

necks would have required a 1.6 ton heart — a tenth of the animal's body

weight. The study proposed that animals like these would have had

rudimentary auxiliary 'hearts' in their necks, whose only purpose was to

pump blood up to the next 'heart'.

While the long neck has

traditionally been interpreted as a feeding adaptation, a recent study

suggests that the oversized neck of Diplodocus

and its relatives may have been primarily a sexual display, with any other

feeding benefits coming second.

Diet

Diplodocus

has highly unusual teeth compared to other sauropods. The crowns are long

|

| The original D. carnegii (foreground) at the Carnegie

Museum (Picture

Source) |

and slender, elliptical in cross-section, while the apex forms a blunt

triangular point. The most prominent wear facet is on the apex, though

unlike all other wear patterns observed within sauropods,

Diplodocus wear patterns

are on the labial (cheek) side of both the upper and lower teeth. What this

means is Diplodocus

and other diplodocids had a radically different feeding mechanism than other

sauropods. Unilateral branch-stripping is the most likely feeding behavior

of Diplodocus, as

it explains the unusual wear patterns of the teeth (coming from tooth-food

contact). In unilateral branch stripping, one tooth row would have been used

to strip foliage from the stem, while the other would act as a guide and

stabilizer. With the elongated preorbital (in front of the eyes) region of

the skull, longer portions of stems could be stripped in a single action.

Also the palinal (backwards) motion of the lower jaws could have contributed

two significant roles to feeding behaviour: 1) an increased gape, and 2)

allowed fine adjustments of the relative positions of the tooth rows,

creating a smooth stripping action.

With a laterally and dorsoventrally

flexible neck, and the possibility of using its tail and rearing up on its

hind limbs (tripodal ability), Diplodocus

would have had the ability to browse at many levels (low, medium, and high),

up to approximately 10 metres (33 ft) from the ground. The neck's range of

movement would have also allowed the head to graze below the level of the

body, leading some scientists to speculate on whether

Diplodocus grazed on

submerged water plants, from riverbanks. This concept of the feeding posture

is supported by the relative lengths of front and hind limbs. Furthermore,

its peglike teeth may have been used for eating soft water plants.

In 2010, Whitlock

et al. described a

juvenile skull of Diplodocus

(CM 11255) that differs greatly from adult skulls of the same genus: its

snout is not blunt, and the teeth are not confined to the front of the

snout. These differences suggest that adults and juveniles were feeding

differently. Such an ecological difference between adults and juveniles had

not been previously observed in sauropodomorphs.

Other

anatomical aspects

The head of

Diplodocus has been widely

depicted with the nostrils on top due to the

|

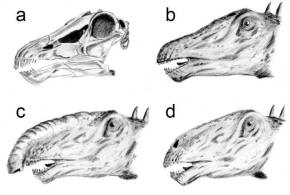

| a) skull, b) classic rendering of the head with nostrils on top,

c) with speculative trunk, d) modern depiction with nostrils low on

the snout and a possible resonating chamber (Picture

Source) |

position of the nasal openings

at the apex of the skull. There has been speculation over whether such a

configuration meant that Diplodocus

may have had a trunk. A recent study surmised there was no

paleoneuroanatomical evidence for a trunk. It noted that the facial nerve in

an animal with a trunk, such as an elephant, is large as it innervates the

trunk. The evidence suggests that the facial nerve is very small in

Diplodocus. Studies by

Lawrence Witmer (2001) indicated that, while the nasal openings were high on

the head, the actual, fleshy nostrils were situated much lower down on the

snout.

Recent discoveries have suggested

that Diplodocus and

other diplodocids may have had narrow, pointed

keratinous spines

lining their back, much like those on an iguana. This radically different

look has been incorporated into recent reconstructions, notably

Walking with Dinosaurs. It

is unknown exactly how many diplodocids had this trait, and whether it was

present in other sauropods.

Reproduction and growth

While there is no evidence for

Diplodocus nesting

habits, other sauropods such as the

titanosaurian

Saltasaurus have been associated with

nesting sites. The titanosaurian nesting sites

indicate that may have laid their eggs communally over a large area in many

shallow pits, each covered with vegetation. It is possible that

Diplodocus may have done

the same. The documentary Walking with

Dinosaurs portrayed a mother

Diplodocus using an

ovipositor to lay eggs, but it was pure

speculation on the part of the documentary.

Following a number of bone

histology studies,

Diplodocus, along with

other sauropods, grew at a very fast rate, reaching sexual maturity at just

over a decade, though continuing to grow throughout their lives.

Previous thinking held that sauropods would keep growing slowly throughout

their lifetime, taking decades to reach maturity.

Classification

Diplodocus

is both the type genus of, and gives its name to

Diplodocidae, the family

to which it belongs. Members of this family,

while still massive, are of a markedly more slender build when compared with

other sauropods, such as the titanosaurs and brachiosaurs. All are

characterised by long necks and tails and a horizontal posture, with

forelimbs shorter than hindlimbs. Diplodocids flourished in the Late

Jurassic of North America and possibly Africa

and appear to have been replaced ecologically by titanosaurs during the

Cretaceous.

In popular

culture

Diplodocus

has been a famous and much-depicted dinosaur as it has been on display in

more places than any other sauropod dinosaur.

Much of this has probably been due to its wealth of skeletal remains and

former status as the longest dinosaur. However, the donation of many mounted

skeletal casts by industrialist

Andrew Carnegie to potentates around the

world at the beginning of the twentieth century

did much to familiarize it to people worldwide. Casts of

Diplodocus skeletons are

still displayed in many museums worldwide, including an unusual

D. hayi in the

Houston Museum of Natural Science,

and D. carnegii in

a number of institutions.

Diplodocus

has been a frequent subject in dinosaur films, both factual and fictional.

It was featured in the second episode of the award-winning BBC television

series

Walking with Dinosaurs.

The episode "Time of the Titans" follows the life of a simulated

Diplodocus 152 million

years ago. In literature,

James A. Michener's

book

Centennial has a

chapter devoted to Diplodocus,

narrating the life and death of one individual.

Diplodocus

is a commonly seen figure in dinosaur

toy

and

scale model lines. It

has had two figures in the Carnegie Collection.

Return to the

Old Earth Ministries Online Dinosaur

Curriculum homepage.

Shopping

Bay

State Replicas - None

Black

Hills Institute - None

|